This chapter is an excerpt from the book I am currently working on titled, “Inner Atlas.” I have decided to nix this chapter entirely and post it here, just so it exists somewhere.

Floating

We had just gotten off the shuttle with about a dozen other passengers at the starting point on the Namekagon River. It was a surreal experience being inside a bus packed with people and inner tubes. However, at this point in my life, anything bizarre seemed completely normal, for I had only recently realized that I had previously taken normalcy for granted.

I braced for the water to be cold, but the sun must have woken up early to warm it. The air was still, and the river was so calm that it begged for a push. Yet, into the water we all went, and five minutes into floating, I knew this was exactly where I wanted to be. The hell was officially over.

The fact that my husband and I were currently on The Namekagon meant something significant had recently occurred. Sadly, dramatic events had been a running theme for the last couple of years, so I shouldn’t have been surprised by our spontaneous vacation. We were here because what I thought would be a never-ending saga finally came to a close when my mother passed away.

My mom’s prolonged battle with severe depression had taken its toll and ruined the last years of her life. I spent that time shuttling back and forth to bring her home from various hospitals, only to see her immediately boomerang into another. Watching from afar was no different than observing up close, for her depression was unconstrained by boundaries and oblivious to distance.

A few days after my mother’s funeral, my husband and I headed north. I knew in advance that cleaning out her house wouldn’t be enough for me emotionally and that I would have to look elsewhere for closure. I finally felt free from all the chaos and wanted to savor the beginning of my new normal. I wanted to see Wisconsin for what it was, not for what I had forced it to be. Going north meant I could step back and see the bigger picture of all that had happened. I was eager to reminisce and see what used to be my present behind me.

I immediately took to the river as a form of therapy. When I wasn’t thinking of anything, I was thinking of everything. My mind alternated from empty thoughts to every thought imaginable. I closed my eyes tightly and then opened them, wondering where I was. I was thrilled at the prospect that my mom’s all-consuming battle wasn’t going to be my war anymore. My thoughts wandered through the past, present, and future, overwhelming me with ideas but lacking a clear direction. Too many ideas combined with no impressions bombarded my brain. I didn’t know what to focus on, so I overthought everything.

I wanted the water to quiet my brain and rescue me from the cacophony of words. The time for thinking had passed; the reflecting hour was upon me. I was living in the now but focusing on everything except the present moment. My mother’s funeral happened several days ago, yet I couldn’t allow that day to recede into the past. I had to give that day one final mental spin before purging it into the abyss. I wanted to absorb the meaning of finality.

As I gently floated down The Namekagon River, I watched the water lazily glide by. The moving stream showed me that thoughts did not matter because what were thoughts to water? The river did not need thinking to guide it, so why was I fretting about making conscious decisions? What did it matter if I didn’t know what the next phase in life had in store for me? I would get to my future whether I thought about it or not. The river only cared about sailing toward tomorrow.

Clearing

My husband Ryan and I cleaned out my mom’s closets the day after her funeral. She had squirreled away so much useless stuff that it was hard to distinguish what was worth keeping. We went through boxes of Christmas decorations, childhood art projects, school science papers, old linens, hordes of nylons, and mountains of clothes. Mostly, though, her closets brimmed with magazines and paperback novels I doubted she ever read. Throughout the house, we found where she hid all the pictures that used to hang on the walls stuffed into drawers or tucked in the back of closets for fear of the cameras she thought were in them. Evidence of her paranoia abounded in the unlikeliest places and reminded me of her frayed mental capacities in her final days. Every misplaced item showed me how far she fell into her private rabbit hole, which grew into a bottomless pit.

We stripped the house of all the crapola before reaching the core of who she was. What was left after all the miscellany was cleared away was her art collection, and that’s when we finally found her. She was an art lover at heart, and her passion for Asian vases was one of the few areas of respite in her restless world. She found her other diversion in gardening, so together, art and gardening were her primary devotions. Depression was a feature of her personality, but it didn’t define her, at least not always. When she wasn’t conquering her demons, she was quite content with her hobbies.

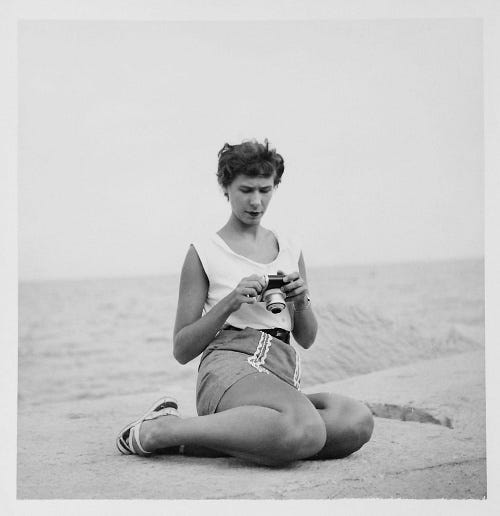

We eventually found time to sit down with the heaps of photographs we discovered in various drawers and closets. I was dumbstruck by how many pictures I had never seen before. There were photographs of both sets of grandparents in their younger years, my father as a baby and my mom as a teenager. For the first time in my life, I saw pictures of my parents when they were both very young. There were many touching photos, but the ones that really stood out were the ones of my parents when they just started their lives together. They weren’t exactly a young couple — they were both in their mid-thirties when they married — but the freshness of their relationship was evident. They looked just as optimistic about their future together as any young couple. Photographs of them holding my sister and me as babies seemed totally normal, with no indication of peril lying ahead. There were photos of my dad on fishing boats, holding a beer in one hand and a cigarette in another. I soon noticed that every photograph of my father had him holding a cigarette in his hand or pursed between his lips. Eventually, the pictures of my father in his adult years trailed off, the cigarettes being a major contributor to his early demise. There were only a few photographs of my father in a wheelchair, slumped to one side, flashing a half-sided smile. Surprisingly, he didn’t hold a cigarette in any of those photos, which was an unfair depiction of him because it failed to document that he continued to smoke like a chimney all the years he resided in a nursing home after suffering a major stroke.

Despite my mom’s struggles with depression, she still managed to live a decent life. Well, everything was going well for her until her husband was unexpectedly incapacitated, and she was suddenly left to her own devices. I was 14 years old when my 56-year-old father suffered a major stroke while sleeping, and for the next 18 years, I only had half of a father due to severe brain damage. My mother was no nurse and couldn’t care for him even though she initially tried. While my father wound up in a nursing home, my mom slowly dangled off a mental cliff.

My mother never called cigarettes just cigarettes; they were always “those goddamn cigarettes,” as in, “All he ever thinks about is those goddamn cigarettes.” She was right to call them that, though, and it was true that smoking was the only thing my father genuinely cared about. I got the impression he believed he didn’t have much to live for, but since smoking gave him some semblance of joy, he threw all his passion into it. He often decided it was more important not to miss the call for a smoke break than it was to hang out with his family, who just rode the bus for 45 minutes to visit him.

My mom never learned how to drive, and my sister left with what used to be my dad’s station wagon when she moved out of the house, so the year and a bit when my mom and I had to bus it to visit him was the most disheartening. Indeed, we both lost passion for seeing him after his constant brushing us aside to go off and enjoy a cig, leaving us to wonder what the point of going there was.

Brain damage is such a mysterious thing. I still don’t know if he was happy, sad, or content. I think he was at least content with his life, and I hope I don’t just tell myself he was. My sister and I were never even sure if he understood that we were his daughters because it more or less seemed that we were just people to him. Every time we looked into his eyes, an oblivious daze stared back at us. Our father was a shell of a man: haunting, empty, and withdrawn. Content? Sure. Maybe he was. I never knew. No one did. Possibly not even him.

I loved my mom, but I always hated her depression. Her brand of melancholy was a foundation of her personality, and some days, she could get a grip on herself, but other days, she could not. As she aged, her depression got worse. Towards the end, her depression took over. It was as though she had a black hole inside her head, and she spent the last two years of her life trying to tuck herself into that dark void of space. Depression made my mom her own worst enemy, and she was determined to suffer severely for the crime of being herself.

Matters were made worse when my dad couldn’t understand that he suffered a stroke. He was convinced his wife maliciously pushed him out of bed and onto the floor. There was no amount of telling him that she had nothing to do with the fact that a blood clot popped inside his brain to make him believe otherwise. His constant saying, “She pushed me,” every time we visited him exasperated her and wore her patience thin.

“He keeps accusing me,” she would say. “It makes me not want to see him.”

I couldn’t blame her for growing resentful, but it shouldn’t have given her a reason to wake up at 5 a.m. and barge into her daughter’s bedrooms and scream at them that she wanted him to die. My sister was two years older than me, and she moved out of the house the moment she turned 18, leaving me alone to endure the full range of her rants. Things weren’t any better when she was in a funk because then she would moan about how she wanted to kill herself. I had to learn to ignore the constant theme of death, but I would be lying if I didn’t admit that my favorite dream was when I saw myself as an orphan. Four years under a roof with a depressive mother was a tough thing to endure, and it made me want to grow up fast so I could get the heck away. I know very well what life looks like when one allows oneself to wallow in self-pity, and I must say that appearance is not very attractive. It looks even less appealing when a parent puts that outfit on and lives in it like a housecoat. I quickly learned that it doesn’t take living near an ocean to be affected by a tsunami. The sea came to us daily, and I had no choice but to swim in it.

My dad eventually died of a heart attack at age 74, but not before having several more strokes and metastatic colon cancer. His life was a tragedy for nearly 20 years, and I always felt helpless to do anything about it. As the years went by, he gradually became one of those unfortunate people residing in a nursing home who rarely received visitors. We loved him, but it became pointless to visit him as often as we used to. In my 20s, my sister and I would see him once a year, and my mom would ride the bus to him about once a month, but I’m sure there were months when she wasn’t motivated enough to even bother. We all eventually concluded that just because his life came to a screeching halt, it didn’t mean ours had to as well. His life fell into a familiar pattern, so we allowed our lives to do the same.

We learned early on that we couldn’t force ourselves on him, but that never stopped us from beating ourselves up with mountains of guilt. I loathed wallowing in guilt, but that bottomless pit of remorse coated my insides like a lining of acid, and I couldn’t purge it. I became one with the rueful feeling and blamed myself for my dad not taking better care of his health. Guilt is weird because it doesn’t have to make sense. The fact that my dad never checked his blood pressure, didn’t watch what he ate, never exercised, and smoked way too much was somehow my fault. I was a terrible daughter for not being there for him, even though he probably didn’t grasp who I was. I was also a horrible daughter for being furiously mad at him for his thinking that he was invincible. There was no escaping the fact that everything got fucked up because he suffered a stroke, and it was impossible not to want to blame him for it. Yet, it was hard to look at his sorry state and want to blame him for anything. His appearance was proof that he suffered the consequences enough for neglecting his well-being, and it didn’t seem appropriate for us to complain about our state of affairs when he was trapped in a body that was of little use to him anymore.

I always wished that there was something more I could have done for him, but there was nothing I could do because I couldn’t live his life for him. I felt sad and guilty for not knowing what role I was supposed to fill. I felt stupid every time I visited him at the nursing home. Sometimes, I just stood there and stared, watching him do nothing in particular. I often thought he never liked it when we visited him. Going there was the epitome of awkwardness, and I hated it for eighteen long years. Sure, there were good moments, especially in the later years when his speech finally improved, but it honestly took too long to reach that point. It was the slow slog that killed us as a family.

In the months before my mother’s eventual death, I started a journal and titled it The Absurdity Of It All. I knew I was witnessing the end stages of mental illness, but I didn’t know how long her decline would last. The journal was the only place where I could freely admit that I wished her depression would end already. Everything about her situation was absurd — from her suicide attempt at age 77, to her insisting on living alone despite her habit of calling the police every time she thought someone was coming down the chimney, to her constant complaining that she had the same Christmas song stuck in her head for over a year, to her fear that the pictures hanging in all the rooms had cameras in them because the CIA was spying on her. It was a fateful fall down the stairs that broke her hip, leaving her in a wheelchair, that officially kicked off the beginning of the end that actually started decades ago. I wish I could say she had Alzheimer’s, but she didn’t. She was stuck in a permanent fit of psychosis. It was as though her mind grew hands and were slowly choking her brain. Every day, the grip grew a millimeter tighter, and the smaller her brain got, the more grandiose her hallucinations became. I couldn’t help but feel sorry for her that she genuinely believed “We were all going to shoot into outer space,” whatever the heck that meant. I couldn’t even encourage her to eat anything towards the end because she was convinced that the “orderlies were poisoning her.” When she did die, the reason was documented as “a failure to thrive,” but the real reason was that she ate herself alive. She had been slowly snacking on herself until the very end when there was nothing left for her to dine on.

Remaining

My mom’s funeral was a small affair attended by her three adult children (two daughters and one son from a previous marriage) and several young grandkids. For years, we siblings played supporting roles as actors in our mother’s all-consuming drama, and we were now allowed to take our bows and step off the stage. None of us had to be our mother’s child anymore, and we could see the view she had been blocking all those long years. Her passing vacated the space she occupied above us on the ladder of family dynamics. I felt my mortality when I psychologically moved up a rung to fill the gap she left behind. Our parent’s turns were over, and it was up to us to stand in their place. Indeed, life is nothing more than a slow climb up that infinite ladder. When we reach the top, our last step hovers in empty space.

I was glad the funeral was over, but thoughts about it kept infiltrating my mind. It was a gorgeous day when we started our float down the Namekagon River. Overhead was a bluebird sky with occasional patchy clouds that would visit just in the nick of time to give our legs respite from baking directly under the sun. We floated lazily past forests filled with small songs of tiny birds we couldn’t see through the thicket of foliage. The air was still, and the float only went as fast as the river moved. We had nowhere to be, and if the water had stood entirely motionless, we still would’ve been going exactly where we intended. I thought many times throughout the float that I would prefer life to go at the pace of that water. I appreciated the river’s lack of urgency, yet I respected its determined focus to never linger. The river understood that to stand still was to stagnate, but to rush was to risk havoc. The river knew it would get to wherever it was heading, and it had all the time in the world to reach its destination. The water took its time and understood the value of listening to songbirds along the way.

Finally, I felt ready to release. I reached into my gut, grabbed all my simmering hatred, frustrations, and fears, and mentally purged them into that watery abyss. I told myself I could see those emotions sink into the murky depths below. I performed no ceremonies. I waved no goodbyes. History quietly disappeared into a liquid grave.

“I think I get it now,” I said to Ryan, who was lying half-asleep on his inner tube somewhere nearby, my words groggily awakening him from a mindless reverie.

“Huh?” he asked.

“I said I think I get it,” I repeated.

“Get what?”

“The meaning of it all.”

“You do?” Ryan perked up. “So, what does everything mean?”

“Nothing,” I said. “There is no meaning. Everything is just life. Until you die.”

“Aw, crap, I could have told you that,” Ryan scoffed and got off his inner tube and into the water floating in the center. “But wouldn’t it be nice if life meant something more?”

I got off my inner tube and got in the water, too. “Sure,” I said, “but isn’t it hubristic for humans to attach meaning to life? Other animals don’t do that, so why should we? We’re all just creatures on the same planet.”

“Oh, I know what you’re saying,” Ryan concurred. “Humans aren’t that great. We’re the main reason why the planet is dying.”

“Hmm, that makes me wonder how that guy on the bus is doing,” I wistfully said.

“What guy?” Ryan asked.

“The guy that kept dying on me every ten minutes!” I declared. “You mentioned dying, and my thoughts went to him. He’s the reason why I’m so tired right now.”

That was a long bus ride from Milwaukee to Minneapolis. We took a night bus between those two cities to save money and didn’t get seats together. The guy I sat next to was in dire need of a CPAP machine that he didn’t have, and his constant suspension of breath made me wonder if he died between every snore. That, and his head kept landing on me. How long was that ride? Six and a half excruciating hours.

“He’s probably doing perfectly fine,” Ryan stated.

“Oh, I’m sure he is,” I agreed. “At least I caught up on some rest out here.”

This entire trip was planned at the last minute when I hastily whipped up an itinerary. Northern Wisconsin was foreign to me, so I did an internet search for any river that offered cabins and tube rentals, hence landing us here on this unpronounceable river whose sky was suddenly demanding everyone’s attention. Right in the middle of our bantering, the coldest, most unexpected shower fell out of an abruptly darkened sky, causing everyone to holler.

People climbed on top of their tubes but quickly jumped off them because exposing one’s head to the freezing rain was better than subjecting a whole body. The river turned into a little shop of horrors as people maneuvered down the water in pure cold agony. The sound of fifty people whimpering would have been hilarious if it was funny, but it wasn’t funny because it was frigid. Where the sky got the ice-cold water from at the beginning of August was a mystery, as it felt like it was water the clouds were saving to make snow with in January. It seemed a little premature for the sky to release its primary ingredient for winter so early, and everyone cursed the clouds for being so impatient.

Ryan and I had never been on this river before, so we didn’t know how much farther the pull-out area was. No one was on their inner tube anymore, and everyone started mad-dashing toward the end. Initially, people were spread across the river’s length but were now in a massive clump of rubber, bodies, and howling. My teeth were chattering, and Ryan’s lips were turning blue.

“This was not what I was expecting,” I whimpered.

“Nope, not even remotely,” Ryan agreed.

When we finally exited the river about twenty minutes later, it felt like we achieved an impossible goal. We stood on the river’s bank and watched the line of people still trying to reach the end, listening to their sounds of collective despair. It was a sound our ears were used to hearing just a little while ago, but we weren’t really listening to it while it was happening. Now that we were actually hearing it, the cries sounded surreal.

“How can a river hurt so much?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said, “but it did.”

We really didn’t need the symbolism that life can be quite shit sometimes, but we got the demonstration anyway. We were chilled to the bone and hadn’t checked into our cabin yet. After two minutes of contemplating the meaning of what we recently endured, we dashed to the car, grabbed our bags, and begged the cabin host to expedite our check-in process. Once inside, we didn’t even ask who wanted to shower first, for we both jumped under the hot water simultaneously. Even a hot shower was cold because we had to keep stepping back to let the other relish the water. After fifteen minutes, we were back outside watching the last stragglers grope their way to salvation.

When we started floating down the river that morning, nothing could have made us get off it. When the cold rain came down, the last place we wanted to be was on that water. The river didn’t change, we didn’t change, but the outside world did. It’s the external influences that affect us most in life. Often, it’s best to endure the storm and make it to the finish line despite the world’s worst intentions. We didn’t allow the rain to bully us to the sidelines, so we managed to see our journey through.

Of course, not everyone would leave with the same epiphanies we were; however, I was confident that no one would forget experiencing this day. It will be impossible to forget how the day started so beautifully but ended so utterly flawed. What made the day remarkable was the lack of transition; it went from happy to sad in an instant. There was no time to process the change; it was simply thrust upon everyone. Life usually involves a more gradual transition, but, alas, not always. Sometimes, an event will mark you and cause you to be an entirely different person in a flash. You can embrace the new you or resist it, but in either case, the change will have irreversibly occurred.

After our day at the river, we took our sweet time driving the rental car back to Minneapolis. We stopped overnight at a city called Osceola and stayed at a little bed and breakfast called the St. Croix River Inn. The property dripped with character and charm as it sat on a bluff overlooking the river. We sipped wine on our balcony and adored the property’s friendly black cat that temporarily adopted us. We sat out there for hours soaking in that view while talking about how small we felt compared to the incomprehensible grandeur before us. There was so much about the world that we didn’t know. What was the point of asking what the meaning of life was when there would never be an answer? The kitty didn’t seem to wonder why she was there; she was just happy some people cared enough to lavish her with attention that evening. She was living for the moment because there were no guarantees the next guests would take to her as kindly. In short, she was doing what we had been doing for the last several days — just soaking in it.

Wisconsin was good to us after my mom’s funeral, and it allowed me to get as much closure as I could’ve possibly hoped to find in four measly days. My outlook on life transformed just enough to reveal a little more of how life truly appeared. We all get snippets of what life genuinely looks like at various stages that eventually allow us to cobble together an entire image. However, until that final picture emerges, all our actions are based on the few pieces of knowledge we gradually obtain.

Everyone starts young and stupid, but only some grow old and wise. Life unfolds in increments, not in leaps and bounds. To live well is to seek knowledge at every phase of transition.

My books Memory Road Trip (e-book or paperback) and Time Traveled (e-book or paperback) are both available!

If this is a true story, you had a hard life as a kid. It was a good, heartfelt read. I enjoyed it. I’ve floated down Apple River in Wisconsin. At that time it was a tradition for Canadian university students, so it was quite different from your float. Maggie

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanx for reading. Yup, it’s all true. I originally wrote it as an opening chapter for my upcoming book, but after rereading it, I think it opens too strongly. I parsed out bits and pieces and wove it into the second chapter. Floating down Wisco rivers is the best!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very well written. I can imagine how you feel knowing the same things about these individuals but witnessing things from my point of view.

I know exactly what you mean by the cigarette being your Dad’s main priority! We would frequently have to wait until he was done with that before our visit. We would just be sitting there and wait. My parents and I visited him for holidays and very frequently at the nursing home. My dad and Bob would talk about fishing, like when they went to Canada for a fishing trip, or what was going on, did he have a good meal, etc. We would bring him some items, usually a treat. He did seem to almost improve as you said as time passed with his speech.

I became quite close with Grandma especially in my late teens and early twenties when I would help take her food shopping to Walmart (where we would have to go by the items as they were on the list – not where they were located in the store) or go to eat with her at Genesis. I tried to take some of the burden off my Dad sometimes to help her since he took care of the house and got her groceries, etc. Her friend, Barbara, had passed away, so she needed more help now. Barbara was a godsend of a person that she was so lucky to have, and I feel that this loss of her best friend was a factor in the increase in her mental health struggles. She was a lot at times. Sometimes we would pick her up to go out to eat for a holiday and she would say “when I die will you come put flowers on my grave”, or other morbid mentioning’s like you have described. She alluded to death very frequently.

We did develop a relationship where we talked about Art, past stories, and we laughed a lot before the bad demise where the worsening depression and schizophrenia took ahold. She would call my parents incessantly at all hours of the day. Call my phone and leave voicemails if I didn’t answer. My Dad tried so hard for her time and time again to get treatment. He would battle the doctors and nurses trying to get them to help her. Place after place. She would “fool” the doctors and only tell family the truth about her true feelings – like the Christmas song, secret cameras and being on a show, everyone being imposters and not their true selves, food bring poisoned. She was so intelligent that unfortunately she had this way to manipulate the doctors and nurses. They would send her home, she would stop the meds, stop letting the nurse come in, and the cycle kept repeating time and time again.

Mental health care is so lacking in this country. I consistently see the struggles of so many resorting to different self-medicating methods when at the heart of the issue they need better mental health care.

I look forward to reading more of your new book! I am so proud of you and admire your accomplishments. And, just so you know, Grandma always did speak of you in high regards with a sense of pride about your talent with art, career, and at this time, the book of Poems that you had recently published. She would also share all the photos of your latest travel adventure with us that you had sent her and put them up around the house.

Love, Nikki

LikeLiked by 1 person

Believe you me, your contributions didn’t go unnoticed. She’d mention to me all the time how helpful you were taking her shopping, etc. She always appreciated you. And, yes, I agree, her mental state got exponentially worse after she lost Barbara. Omg, those two would run around and do everything together. I’m honestly surprised they never got into a car accident—that lady couldn’t drive for shit. She could never park the car straight either, and she’d leave half of it sticking out into the road whenever she parked in the driveway. They would laugh a lot, though, which I’m sure was something they both needed to do. (Barbara’s husband killed himself. Did you know that? They had two teenagers at the time. If I remember correctly, he did the carbon monoxide in the car/garage thing.) Okay, here’s a funny story: Once, they went to visit my dad at some hospital (I think it was Froedtert), and they took the elevator to the incorrect floor and started walking around. A group of male doctors stopped them and told them they were on the wrong floor—told them they were on the doctor’s floor—and they needed to turn around. My mom said she looked at “all the cute doctors” and said, “I don’t know, but this looks like the right floor to me!” Then, the two of them started giggling like teenagers. She could be funny sometimes. I think she liked adults better than kids. I always suspected she hated being a mom. Growing up, all I ever saw was her mean and depressive side. She was exhausting to be around. Did you know she was a good artist? She never did anything with that talent, though. She was also her high school’s Valedictorian. Gosh, she harbored so much wasted potential. Mental illness is a bitch. Did you know her mom was institutionalized? Apparently, it happened right after she was born, like, literally right after she was born. She handed her baby (my mom) to her sister and said, “Here, this is yours.” Her aunt then raised her. So, yeah, lots to unpack there…

LikeLike